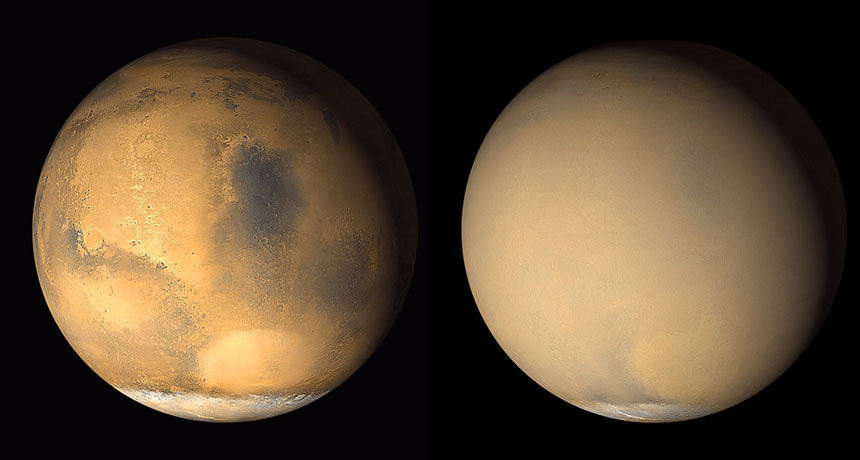

Massive dust storms are robbing Mars of its water

Storms of powdery Martian soil are contributing to the loss of the planet’s remaining water.

This newly proposed mechanism for water loss, reported January 22 in Nature Astronomy, might also hint at how Mars originally became dehydrated. Researchers used over a decade of imaging data taken by NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter to investigate the composition of the Red Planet’s frequent dust storms, some of which are vast enough to circle the planet for months.

During one massive dust storm in 2006 and 2007, signs of water vapor were found at unusually high altitudes in the atmosphere, nearly 80 kilometers up. That water vapor rose within “rocket dust storms” — storms with rapid vertical movement — on convection currents similar to those in some storm clouds on Earth, says study coauthor Nicholas Heavens, an astronomer at Hampton University in Virginia.

At altitudes above 50 kilometers, ultraviolet light from the sun easily penetrates the Red Planet’s thin atmosphere and breaks down water’s chemical bonds between hydrogen and oxygen. Left to its own devices, hydrogen slips free into space, leaving the planet with less of a vital ingredient for water.

“Because it’s so light, hydrogen is lost relatively easily on Mars,” Heavens says. “Hydrogen loss is measurable from Earth, too, but we have so much water that it’s not a big deal.”

Previous studies have indicated that Mars, which was once covered in an ocean about 100 meters deep, lost the bulk of its water through hydrogen escape (SN Online: 10/15/14). But this is the first study to identify dust storms as a mechanism for helping the gas break away. The total effect of all dust storms could account for about 10 percent of Mars’ current hydrogen loss, Heavens says.

Whether that was true in the past is up in the air. Extrapolating back billions of years ago, when Mars was warm and wet, isn’t so easy. Scientists don’t know how dust storms would have worked in a wetter climate or a thicker atmosphere.

“Variations over weeks or months don’t really tell you anything about the 1,000-year timescale that governs hydrogen,” notes Kevin Zahnle, an astronomer at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., who was not involved in the study.

But Zahnle, an expert on atmospheric escape of gases, agrees with the main thrust of the study: Right now, dust storms are helping to bleed Mars dry.