A new kind of spiral wave embraces disorder

A type of spiraling wave has been busted for disorderly conduct.

Spiral waves are waves that ripple outward in a swirl. Now scientists from Germany and the United States have created a new type of spiral wave in the lab. The unusual whorl has a jumbled, disordered center rather than an orderly swirl, making it the first “spiral wave chimera,” the researchers report online December 4 in Nature Physics.

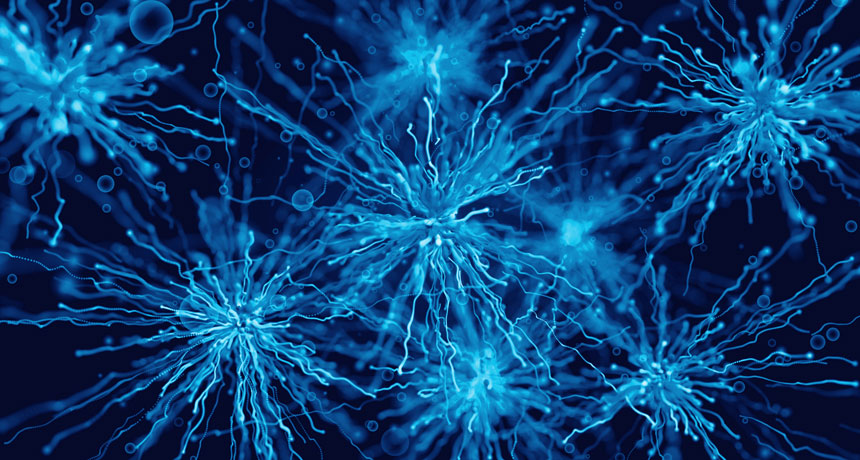

Waves, which exhibit a variety of shapes, are common in nature. For example, they can be found in cells that undergo cyclical patterns, such as heart cells rhythmically contracting to produce heartbeats or nerve cells firing in the brain. In a normal heart, electrical signals propagate from one end to another, triggering waves of contractions in heart cells. But sometimes the wave can spiral out of control, creating swirls that can lead to a racing or irregular heartbeat. Such spiral waves emanate in an orderly fashion from a central point, reminiscent of the red and white swirls on a peppermint candy. But the newly observed spiral wave chimera is messy in the middle.

Harnessing an oscillating chemical process known as the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction, the researchers created the wave using an array of small beads, each containing a catalyst for the reaction. When placed in a chemical solution, the beads acted as individual pulsating oscillators — analogous to heart cells — in which the reaction took place.

The researchers monitored the brightness of each bead as it alternated between a fluorescent state that emits red light and a dim state. Because the reaction is light sensitive, illuminating individual beads allowed the researchers to induce nearby beads to sync up. Thanks to that syncing, a spiral wave took shape. But, unlike any seen before, it had a muddled center.

The wave is a new kind of “chimera,” a grouping of oscillators in which some sync up, but others march to their own drummer, despite being essentially identical to their neighbors. Although researchers have previously created other kinds of chimeras in the lab, “it’s a step further to show that you can have this in even more complex setups” such as spiral wave chimeras, says Erik Martens of the Technical University of Denmark in Kongens Lyngby, who was not involved with the research.

While spiral wave chimeras had been predicted theoretically, there were some surprises to the real-world curlicues. Single spirals, for example, sometimes broke up into several independent swirls, each with disordered centers. “That was quite unexpected,” says chemist Kenneth Showalter of West Virginia University in Morgantown, a coauthor of the study.

It’s still not known whether the chimera form of spiral waves can appear in biological systems like the heart or the brain — but the new whorl is one to watch out for.